018. Delegated Discernment PART 2 | Why does Zara look like that ???

The growing gap between curation and conviction, and how that gap shapes the way shopping looks

Good evening! Thank you for allowing me back into your inbox and for a lovely response to my last email. It wasn’t written as a “part one,” but it’s become one, because today I’m coming to you with a part two.

Part one established delegated discernment as a condition of contemporary taste-making. Part two turns to its consequences. Specifically, the difference between curation and conviction, and how the privileging of the former shows up in e-commerce !!!! how FUN.

Curation & conviction.

Despite being governed by entirely different relationships to choice and commitment, conviction (“omg i luv this thing”) and curation (“look at all these things i luv, they represent me”) tend to collapse into one another in conversations about taste — particularly as it relates to fashion and style.

In this context, conviction is the practice of making and sustaining a choice, even in the absence of consensus. It accepts the possibility of being misunderstood or mistimed because it is less about being right than it is about being sure. Conviction produces a point of view not because it is flawless, but because it is owned. In the context of taste, conviction turns preferences (I like this) into patterns (this is me / mine).

Curation, by contrast, is the assembly of selections to reflect back a certain sensibility. Rather than privileging a single commitment, curation organizes, references, and aligns with a set of value signals. It prioritizes coherence and recognition over risk, often selecting from what is already legible and circulating. In the context of taste, curation allows one to establish proximity to what is “good” while avoiding the labor of creation.

As fashion internet dwellers, saving, organizing, and presenting (whether to an audience or to oneself) has become a familiar mode of self-presentation. It’s a way to rehearse identity, signal fluency, and project aspiration without requiring immediate action (or spending $$$). This often reads as diligence or restraint, saying: “I’m not buying everything I like, but I can assemble enough of it to demonstrate what and who I am… even without owning it all,” and, in many cases, it is genuinely thoughtful.

But it also allows for conviction to remain optional.

If you don’t need to own the objects of your desire — only gesture toward them convincingly enough to extract meaning or social value — you can become fluent without ever becoming decisive. In other words, when taste is built primarily through reference, preference never has to fully harden into selection.

The irony, of course, is that conviction is what produces taste worth curating. But, once a system exists to distribute certainty efficiently, fewer people need to practice it themselves (see: delegated discernment part 1).

Back door, side door.

If we accept that we are in an era marked by such a condition, then it follows that a meaningful share of consumers no longer encounter brands through the front door. They arrive through back and side entrances — an unofficial TikTok endorsement, a link in a trusted newsletter, a screenshot dropped in an Instagram broadcast channel… even paid partnerships can circumvent the brand's owned storytelling. By the time the shopper lands on a product page, the work of evaluation has often already happened elsewhere.

Today’s e-commerce is styled to accommodate these points of entry.

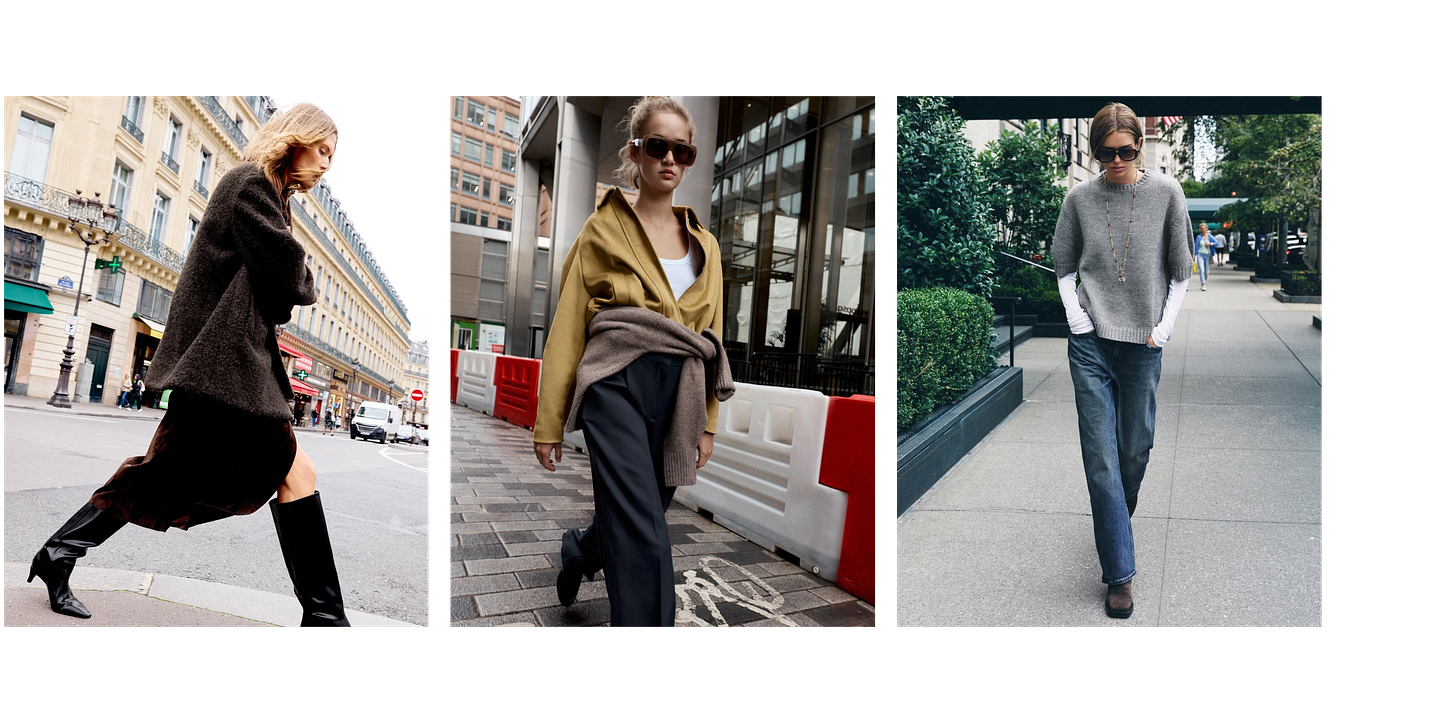

When discovery is centralized — through search, traditional ads, or a store/homepage— brands are solely responsible for articulating value. When discovery is fragmented and relational, their merchandise is often framed by external context: who shared it, where, and what else it appeared alongside. As this becomes a dominant mode of discovery, brands are no longer just selling stuff; they are situating their wares within a constellation of references their consumers already recognize, own, or aspire to. Making it possible, even likely, to see a sweater photographed on a street you’ve seen dozens of times on Instagram or a coat styled with a bag the brand doesn’t even sell.

And yet, these surrounding cues don’t compete with the product, they stabilize it — signaling where it belongs before asking whether it is wanted.

If consumers arrive with judgment partially pre-conducted & outsourced, the brand’s task is not to overwrite their taste, but to mirror it back legibly. The product is offered not as a standalone proposition, but as something that already fits within an existing mental map of aspiration & understanding. In this setup, the consumer can ask “Does this align with what I already recognize as me /mine?” rather than merely, “Do I want this?”

Consequently, e-commerce begins to resemble the same curated environment that led the consumer there in the first place — not because brands have become tastemakers, but because they are responding to an audience that expects consumption to be relational and curated.

Retail, then, operates as both desire creation and desire maintenance.

But why does it look like that?

Traditionally luxury-coded signals (minimalism, high-status talent, editorial-style imagery) are a kind of shorthand that can tell the consumer: “this belongs in the same mental category as the things you already trust or want.” This is less about mass brands trying to “become” luxury (or “craftwashing”), and more about accommodating side-door entry as the dominant mode of discovery.

When a COS cardigan, a Khaite cardigan, and a Zara cardigan are earnestly recommended by the same creator, in the same apartment, next to the same pair of $200-something jeans, the distinction between them becomes contextual rather than categorical. What matters is not what the brand is, but how the product appears at point of purchase. Oftentimes, luxury-esque aesthetics allow mass products to move smoothly through the same cultural circuits as more overtly aspirational brands.

Creators and tastemakers are central to this condition.

By encountering products through people first, a consumer can bypass the brand layer altogether. It is in brands’ interest, then, to meet consumers where taste has already been assembled —mirroring familiar references, echoing established cues, and signaling compatibility. If successful, little assessment is required beyond price. Trust precedes evaluation. Recognition precedes desire.

In this system, luxury is a language that mass (and aspirational) brands can use to ensure their products travel smoothly through fragmented, person-led discovery environments.

If conviction once lived at the point of discovery, it has now been redistributed across platforms, people, and contexts; retail is just one node in that circuit. Brands no longer needs to use their sites to persuade us to believe, but to meet us where belief has already been assembled. And so, to appear aligned is often enough to reap the rewards of alignment (aka a sale).

Thank you for reading my first email of 2026. I can’t quite believe how many of you found your way here in 2025 🥹 If you’re newer to the party, my hope is that you experience Wardrobe Thirteen the way you would a well-loved, well-considered wardrobe.

Some pieces are standalone statements, meant to be worn often and remembered easily. Others reveal their value more slowly, best understood alongside what came before or what’s still to come.

My writing has always been highly referential (even to myself) & informed by a post–master’s thesis boredom (see: Jean Baudrillard Simulacra/Simulation reference above), so you may need to go digging about to get to the goods.

THANK U FOR LOVING MY WARDROBE, please do stay a while.

Wealth of knowledge!

This is so well-articulated and true, Rebecca!! And I am not just saying it bc it's referencing my writing haha well done :)